The founding father of Zionism, Theodore Herzl, was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist and founder of the World Zionist Movement. The first headquarters of the Zionist movement were in Germany.

With the defeat of Germany in WW1, and the granting of a British Mandate over Palestine by the League of Nations and the Balfour Declaration guaranteeing a Jewish national home in Palestine, the headquarters of the Zionist Movement moved to Britain. The new Zionist leadership was led by Prof. Chaim Weizmann in London.

A Visit That Changed History

The idea of reviving a Jewish national home after 2,000 years of exile seemed almost overwhelming. A group of very strong women, whose husbands were involved in Zionist activity, felt that women should have a distinctive and equal role in the return to Zion. Some of these women were also suffragettes, struggling for the political right of women to vote alongside men in England.

These women, led by Rebecca Sieff, Vera Weizmann and Romana Goodman, wives of prominent Zionists and powerful personalities in their own right, founded a “Ladies Committee” within the British Zionist Federation in 1918. On January 12, 1919, they held the founding conference of a Women’s Federation in Britain in London for the purpose of setting up a Women’s Federation in Britain. This eventually became known as the Federation of Zionist Women, later British WIZO, and today WIZO UK.

(In the photo: Rebecca Sieff)

In 1918, three of the founders, Rebecca Sieff, wife of Israel Sieff, the Zionist movement’s Political Secretary, Dr. Vera Weizmann, wife of Zionist movement President Chaim Weizmann, and Edith Eder, wife of Zionist leader Dr. Eder, had the opportunity to participate in a Zionist Commission visit to Eretz Israel/Palestine, to see the unfolding reality with their own eyes. What they discovered shocked them to the core. Following WWI, the Jewish population in Palestine had dwindled due to expulsion, disease and famine. The situation of women, both the chalutzot (pioneers) and the city women from the old yishuv (pre-state Jewish community) was unbearable. They were suffering both physically and spiritually.

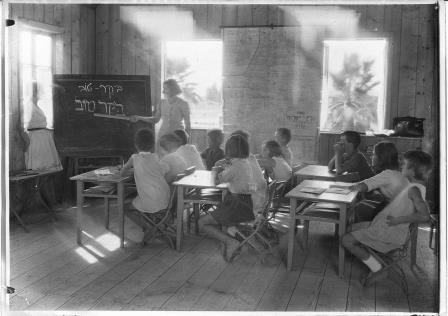

(In the photo: 1923 – Chaim Weizman in a meeting with girls in home economics and agriculture courses in Tel Aviv)

The Founding of World WIZO

The three women decided they had to found an international organization of Zionist women to confront this situation. Thus the founding conference of World WIZO (Women’s International Zionist Organization) was held in London on July 11, 1920. Rebecca Sieff gave rein to her ideas, and the outline of activities for the new international organization. She spoke at length on the idea that women should work together in an organized fashion, and in doing so, their abilities and powers would develop.

She felt that women should work within an independent framework, but in cooperation with their male comrades – for the rebuilding of the Zionist home. In order to realize the dream of the establishment of a national home, women — via education and training — had to develop their own specific abilities, so as to play the most useful role possible.

They appealed to the Yishuv in Eretz Israel “to take cognizance of the particular approach of women, stemming not from motives of prestige, or privilege, but in answer to genuine needs, and to ensure functioning on a firm basis.”

The proposed areas of activity: “Education, Home Economics, Legislation, Health and Social Services. All are areas which are completely neglected in Palestine and to which only an organized body can hope to bring about change.”

Strong emphasis was placed on agriculture (through the influence of Chana Maisel-Shochat) as the first step towards a national revival. There was a demand to establish agricultural schools, which would provide the training for women to become efficient agriculturalists. Training would also be given on the domestic aspect of rural life, “Training is vital for the farmer’s wife.” However, at the very first conference, the discussion about women led inevitably to a discussion about children and the following priorities were outlined:

a) A desire to help women go out to work, by providing alternative care for children

b) A desire to help women fulfill their function as a mother to the best of their ability, by providing them with professional guidance in child care and nutrition

They appealed to the Yishuv in Eretz Israel “to take cognizance of the particular approach of women, stemming not from motives of prestige, or privilege, but in answer to genuine needs, and to ensure functioning on a firm basis.”

The part played by the founders in carving out the aims of the organization cannot be emphasized highly enough. The personal interests and experience of these women defined the areas of activity within the new organization.

Each woman took note of needs within her field of expertise. Edith Eder, an educator, placed strong emphasis on the area of education, which did not reflect the needs, and reality of the country.

Dr. Vera Weizmann, a medical doctor, noted the high rate of infant mortality and the poor state of health amongst the women and children.

Rebecca Sieff wanted to see the women organized, active, and equal to the men. The striving for equality provoked a discussion at the Conference, on the position of Jewish women in Jewish law. The difficult aspects, and the laws which bore down hard on the woman were stressed, and hope was expressed that a central Rabbinical Authority would emerge that could deal with these problems.

(This subject does not appear in the constitution of WIZO, possibly because of the diversity of opinions among the participants. We therefore find that activity in this area was delayed for many years). The platform focused on vital areas of training for women who arrived in Eretz Israel unprepared for the prevailing needs. These areas included home economics, articulation and the welfare needs of children.

The constitution of WIZO has undergone many changes and additions, but the central basic aims have remained constant, their interpretation and implementation have always been characterized by a flexible approach. From the outset, it was decreed, “The type of work being undertaken by WIZO must change in keeping with changing conditions.” It is this flexibility which has been a source of strength to WIZO throughout all the years of its activity.

As a concrete expression of the constitution, a detailed plan of work was decided upon at the first conference in Carlsbad in 1921.

The resolutions that were adopted for practical action in Eretz Israel were:

a) The establishment of a home for immigrant girls

b) The establishment of an agricultural school for girls

c) Provision of kitchen equipment for the girls school in Haifa

d) The establishment of a center for the care of babies

In order to raise funds for implementing the plans, it was decided to set up a Jewelry Fund, with Lady Samuel at its head. This decision was taken due to the difficulty in transferring money from one country to another, and also because they felt it was important for every woman to make a sacrifice for Eretz Israel.

The Hebrew Women’s Organization

As these developments were taking place in Europe, the women in Eretz Israel also began to organize to further their goals and defend their rights. “Associations of Women” were founded in 1917, a “League of Women for Equal Rights in Eretz Israel” in 1919, and the “Hebrew Women’s Organization” (Histadrut Nashim Ivriot) was founded in 1920. Soon these organizations began to have a working relationship with, and to receive support, from World WIZO.

“The type of work being undertaken by WIZO must change in keeping with changing conditions.”

WIZO’s Activities During Its Early Days

Tipat Halav (‘A Drop of Milk’) Baby Welfare Clinics

The first baby welfare clinics opened in Jerusalem. Many women gave birth and reared their children in the most abject sanitary conditions, without medical intervention, and in conditions that that endangered the lives of the mother and her baby. Added circumstances such as a shortage of doctors, inadequate hospital facilities, a difficult climate, a water shortage in Jerusalem and lack of suitable nutrition led to a high rate of infant mortality. Individual volunteers tried to help, without much avail.

It was Dr. Helena Kagan who pioneered the way to providing medical aid and guidance. She would visit the neighborhoods of the Old City of Jerusalem giving help where necessary and sharing advice. But she could not possibly give all the assistance that was needed. Many women did not seek medical help nor go to the hospitals, due to lack of knowledge or superstition.

Against this background, Batsheva Kesselman conceived the idea of an organization of women. It was decided that this organization (the HNI) would help Hadassah to give medical assistance to pregnant women and babies, it’s main contribution being the establishment of Baby Welfare Clinics. The HNI would speak to the women, persuade them to be examined by a doctor during their last months of pregnancy. The women were encouraged to give birth in hospitals, or visits were made to those women who chose to give birth at home. There were also follow up visits to the women who chose to give birth in the hospitals. All this was carried out with the full cooperation of Hadassah, which provided the medical assistance, whilst the women of HNI would give guidance and provide the general care.

During the daily meetings between the members of the HNI and the women in the neighborhoods, it soon became clear that it was not enough to deal with the pregnant women and the new mothers, but that guidance should also be given to include the rearing the newly born infants. Since it was impossible to burden ‘Hadassah’ with ongoing daily care, the HNI decided to set up advisory clinics. The first such clinic was opened in a room in the Old City of Jerusalem on the twenty third of June, nineteen twenty one. Dr. Helena Kagan worked there, voluntarily, as a pediatrician. She was helped by Batsheva Kesselman, who held overall responsibility for the clinic.

A second station was opened, shortly afterwards, in a shed on the grounds of Hadassah Hospital, which was then known as the Rothschild Hospital. At the beginning, there was a weak response from the women, who had expected to come to the clinics and receive material assistance. To their dismay, they were only given advice from the doctor, so they stopped coming.

A main problem amongst the new mothers was a lack of milk for breast feeding, which was a result of inadequate nutrition. Dr. Kagan taught them how to help themselves by supplementing their feed with cows milk. However, due to financial constraints, most women could not afford to buy cow’s milk, and it was decided to distribute milk. The HNI was given a meager budget for the distribution of milk. In the beginning, each district chairman in Jerusalem was responsible for distributing the milk in her area. However this was not effective and it was decided to distribute the milk at the baby welfare clinics. When the milk was distributed in the clinics, the number of women who visited the clinics sharply increased and larger sums of money had to be allocated.

For the first time the HNI faced the main problem of a lack of economic resources and money had to be found from various sources. Thus, for example, Flora Solomon, wife of a senior official in the Mandatory Government, contributed £25 a month for this purpose, on condition that this task would remain as her responsibility. In a special agreement that was drawn up with the HNI gave her responsibility for the distribution of the milk, assisted by members of the HNI.

The activities at the clinic included, besides the actual distribution of milk, ensuring the cleanliness of the cowshed, the pasteurization of the milk, bacteriological and chemical examinations, and the preparation of formulas according to the direction of the doctor, and adding sugar and water for each baby. The whole enterprise was given the name, ‘Tipat Halav’ (‘A Drop of Milk’) and was located at the Baby Welfare Clinics. When they received the milk, the visiting women would also receive advice and the medical services of a doctor. Thus, the combination of the two, led to the increased awareness of medical services amongst women, and it meant that they received correct advice regarding nutrition.

Gradually the name ‘Tipat Halav’ took over in the Baby Welfare Clinics, and over a period of time, the concept included weekly consultations with the doctor and nurse.

Social Work

From the very beginning, the HNI pioneered social welfare work in Israeli society. Examples include the Baby Welfare Clinics and Tipat Halav clinics, as well as the projects to help the needy such as the Sewing Circles, Committee for the Distribution of Clothing and the Care of Abandoned Children.

Providing help for one’s fellow man was not new to Jewish culture. The innovations made by the HNI lay in their work methods and their concept regarding the quality of social work. According to this concept, the needy should not be given charity, but they should receive what is owed to them as members of the community, i.e. not philanthropy, but constructive aid.

The aim was not to give a lot of aid, but to cause the numbers of those requiring aid to decrease. This change in intent became termed as ‘social work’ rather than ‘tzedaka’ (charity), or ‘nadava’ (alms).

Henrietta Szold contended that the correct meaning of ‘Social Work’ is ‘working for the good of the whole community’ including education and health. If all the factors are not taken into account it cannot be classified as ‘social welfare work’. The members of the NHI saw the work as being Zionistic in every aspect.

The ideas that were proposed by the HNI ran into opposition from some groups of the old settlement. The groups felt that various societies that were already giving help and charity were being overlapped, such as The Gemillat Hassadim (Benevolent Society) Linat Zedek (Free Lodging Society), Ezrat Nashim (Help for Women) etc.

There were other circles which did not look kindly upon the idea. The word ‘help’ aroused antagonism, as the new pioneers saw it as symbolizing the old ways of distributing charity, which was inconsistent with the image of the modern Jew, who was self sufficient.

For example, the Agricultural Center declared a ban upon clothes that arrived from America for distribution to the needy, feeling that this was in direct opposition to the community of workers in the country. Their opposition led to a change in tactics. With the consent of Hadassah, which organized the collection of clothes abroad, it was decided to sell them at low prices. This was the beginning of the ‘Beged Zol’ (cheap clothing) enterprise. This is just one example of providing constructive help, not just being philanthropic for its own sake!

Agricultural Education and Schools

The training of women in agriculture was seen, by the founders of WIZO, as part of the Zionist endeavor. In order to build a normal nation, a certain proportion of men and women must till the soil. ‘At the core of our aspirations for Eretz Israel is the creation of a free, Hebrew, functioning settlement, mainly a settlement of agricultural workers, which will plant hardy roots in the soil to serve as a strong basis, economically, physically, spiritually and politically, for the entire nation.’ By working in agriculture, the women would be a resourceful factor.

One of the basic principles of WIZO was, (and is) to encourage women to be independent and productive in every possible area. Combined, these two motives led to a preference for agriculture, ‘Our dream of dreams is to see a Jewish farmer, his wife by his side, both trained to work in agriculture in Eretz Israel’.

Since Jews in general, and Jewish women particularly, had not worked in agriculture in their countries of origin, they had to be provided with training. There was, at the time, one agricultural school for boys, Mikveh Israel (which was founded in 1870) but no girls were accepted there.

Agricultural training for women began in the Maon (‘Home’) – later to be known as ‘The School for Home Economics’, with Hanna Maisel Shohat as the principal. Courses were held on growing vegetables and flowers, cultivating bees, and lessons in home management.

Agricultural Farms

During the 1920’s, the Moetzet Hapoalot (Women’s Council), the Jewish Agency and the Jewish National Fund (which allocated land) set up six training farms for women, which were known as Working Women’s Farms.

They were set up in order to provide training, over a period of two years, in all fields of agriculture. The farms were in Nachlat Yehuda (1922), Shechunat Borochov, Petach Tikva (1923), Talpiot Jerusalem (1924), Hadera (1925), Mula (1926). Funds were needed for housing and for work apparatus, which the Moetzet Hapoalot were unable to provide. It was at this point that WIZO went into action, the initiative being a joint one.

The farm at Mula was the first to benefit from WIZO’s support. This small farm was established in 1926, with a group of 17 girls, at the initiative of Moetzet Hapoalot and the Department of Agriculture in the Zionist Executive. The farm suffered many problems, lack of water, unsuitable soil, Arab environs. The Department of Agriculture gave little financial support, and the farm was on the verge of closing down.

In 1927, the WIZO Federation in Argentina took the farm under its sponsorship, pledging to supply its needs and to assist in its development. (In exchange, the Federation was released from making payments to the general budget of WIZO. It was the first such arrangement of its type, and did not last long!) Sara Malchin, (a pioneer who was trained at Kinneret) was appointed as Principal.

A few decades later, in the 1940’s boys were also accepted. Financial difficulties continued, and in 1952, when the Moetzet Hapoalot relinquished its share of ownership, the agricultural farm became a Gadna Farm, in an agreement with the Ministry of Defense, and boys received pre-army training, together with agricultural training.

This program lasted for four years, when it was decided that the WIZO federation of Argentina, the Ministry of Agriculture, and the Ministry of Education with the help of the Jewish Agency, would convert the farm into an agricultural high school, which would serve the settlements of new immigrants that surrounded the area. Today, it also serves as a boarding school for children from other areas, or from families who are under the care of the welfare authorities.

In 1928, Moetzet Hapoalot asked WIZO to help with the upkeep of other farms, due to ongoing financial problems. A decision was reached in which three other farms that had trained women, Shechunat Borochov, Nachlat Yehuda and Petach Tikva, were transferred to WIZO in 1930. The American organization, Pioneer Women, undertook the financial maintenance of the other farms belonging to Moetzet Hapoalot.

Vegetable Gardens and Travelling Madrichot (Teachers)

WIZO’s agricultural training did not begin and end with agricultural schools. Anna Jaffe, Rozia Yevnin and Freda Meyerov set up WIZO’s Training Department in 1927, in order to extend agricultural education beyond the confines of WIZO’s educational institutions.

The first madrichot (teachers) were graduates of the “School for the Study of Housekeeping and Agriculture”. (The Maon”). They taught gardening in Tel Aviv. They also taught home economics and kitchen management, in kibbutzim, in addition to vegetable growing. A third realm of activity was to teach ‘Gardening for children,’ to madrichot in schools and nursery schools.

Activities Related to Agricultural Training:

One of the activities that most suited the needs of the time was the cultivation of vegetable gardens. This period, 1926-27, was a period of economic crisis. The economic crisis had begun a short time after the Fourth Aliyah arrived from Poland, and many families were reduced to utter destitution.

Freda Meyerov appealed to the WIZO Executive in London, stating that “not only do women have to take the fullest advantage of the little money that they have, but they also have to be taught how to make a few extra pounds’. One way to save money was by growing vegetables in their back yards, because in this way they can invest the little money they have and make it fruitful. During the times in the seasons when vegetables and fruit were plentiful, they could be made into preserves.

“Is not one of the aims of WIZO to educate women towards life digging the soil, and for home-making? It seems natural to expand this activity to include women in the towns too. Could not WIZO send experts in gardening, and home management, in order to teach these women?”

In terms of concrete assistance, she asked WIZO to send instructions, written and verbal, on the laying of gardens, the rearing of poultry, cultivating bees, etc. “Here, too, it is advisable to organize popular lectures every now and then on these subjects, for small groups of women living in the suburbs.”

It was agreed to grant a trial period for the plan and the modest sum of £100 was allocated. Meyerov, together with Yevnin, who had studied agriculture in Berlin, themselves went out to persuade housewives of the benefits of vegetable-growing, since most of the women did not have the faintest idea of how to work the soil, or how to grow vegetables.

In the Tel Aviv area, the neighborhoods selected for the experiment were areas that were settled by workers. The homes were shacks, surrounded by sand dunes. “WIZO’s Training Department, in addition to guidance, provided the women with seed, fertilizer and rich soil, even giving them small, long-term loans in order to cover initial expenses.

Despite all this, the madrichot at the beginning were met with evasion and reservation, sometimes even ridicule, on the part of the women. “On these drifting sands, nothing will ever grow,” they argued. “Just leave us alone.”

Slowly and gradually, their distrust was overcome, and a few women were prepared to try out the suggestions. Patches of sand were marked off round the shacks (usually with empty cans) and black fertile soil was brought in and spread over the sand.

Two madrichot, who had been trained at the ‘Maon’, and were under the supervision of the ‘Maon’ gardener, set out three times a week to visit the 20 gardens, that were participating in the program.

In 1928, the garden produce was exhibited in a show, and it drew the attention and interest of the whole country. Many women immigrants did not know how to use this produce (or ‘grass’ as it was dubbed by the Polish immigrants). The abundance of produce also raised the problem of what to do with the surplus. It was decided to teach the housewives how to cook the vegetables (see Chapter on Nutrition). The practical aspect of this endeavor was clearly revealed when, in 1929, the Arabs, who were the chief suppliers of fruit and vegetables, boycotted the Jewish shops. These new gardens then became the sole source of vegetables.

A graphic description of the work of the madrichot, and the development of this project, can be found in a letter written by one of the madrichot, and sent to the Instruction Department on the tenth anniversary of its opening.

” …The madricha would go from place to place, visiting each garden, according to a plan. Where the work was not progressing sufficiently, she herself, took up the garden tools, prepared the soil, and created some form of garden, helping to plant seedlings or seeds, and outlining to the woman what she had to do before the next visit. Then she would go on to the next garden. There were many obstacles along the path of the madrichot. A shortage of essential means, apathy, and even recrimination on the part of the women in the event of failure, sometimes defiance, which was accompanied by the reaction “It is not worth it.”

“Yet, despite all, both the madricha and the women saw the fruit of their labors. The contrast between the waste land, covered with thorny bushes and drifting sands, and the tidy gardens of the homesteads, highlighted the joy in creativity that went hand in hand with the hard work. Especially the joy of the new settler, not long in the country, who had had no idea of how or where to begin. With patience and perseverance, the madricha won her over, and succeeded in teaching her agriculture, which was so alien to her. The madricha could indeed feel a sense of accomplishment.”

All in all, it was obvious that the vegetable gardens served a number of purposes:

- Economically – saving money in the family budget, and/or increasing the budget when the housewife grew more vegetables than her family required, and then sold the surplus.

- Fostering a bond between the soil and the women immigrants, and helping the immigrants to adjust to alien conditions.

- Teaching the women to become manufacturers, and not only consumers.

- Enrichment of the family food basket, with items that formed the basis of healthy nutrition.

Disappointment with the response of adults to vegetable growing led to the idea that one should begin to develop an affinity towards plants and greenery at an early age. “And so we arrived at the idea of teaching in the kindergartens. The children, we hoped, would inspire their parents with their spirit, prodding them on.”

The idea spread quickly, first to Haifa and Jerusalem, and later to a few of the larger urban settlements. In 1929, the Training Department conceived the idea of extending its sphere of activity to nursery schools. Thus, from an early age the children would be linked to the soil, through working it, teaching them to love gardens, “as future pioneers, who would conquer the wilderness.”

In 1929, it appears that the number of children receiving instruction in Tel Aviv was 1,400, which was 30% of the total number of children in elementary schools. 700 children in kindergartens were involved, as well as 400 in Jerusalem.

The madrichot, after being trained, were integrated into the program, helping with the work, attending once a week.